2. Input threats

Edit page2.0. Input threats - introduction

Category: group of input threats

Permalink: https://owaspai.org/go/inputthreats/

Input threats (also called “threats through use”, “inference-time attacks”, or “runtime adversarial attacks”) occur when an attacker crafts inputs to a deployed AI system to achieve malicious goals.

Threats on this page:

- Evasion - Bypassing decisions

- Prompt injection - Manipulating behaviour of GenAI systems

- Sensitive data extraction:

- Model exfiltration

- AI Resource exhaustion

Controls for input threats in general

These are the controls for input threats in general - more specific controls are discussed in the subsections for the various types of attacks:

- See General controls, especially Limiting the effect of unwanted behaviour and Sensitive data limitation

- The controls discussed below:

#MONITOR USE

Category: runtime information security control for input threats

Permalink: https://owaspai.org/go/monitoruse/

Description

Monitor use: observe, correlate, and log model usage (date, time, user), inputs, outputs, and system behavior to identify events or patterns that may indicate a cybersecurity incident. This can be used to reconstruct incidents, and make it part of the existing incident detection process - extended with AI-specific methods, including:

- Improper functioning of the model (see #CONTINUOUS VALIDATION, #UNWANTED BIAS TESTING)

- Suspicious patterns of model use (e.g., high frequency - see #RATE LIMIT and #OVERSIGHT).

- Suspicious inputs or series of inputs (see #ANOMALOUS INPUT HANDLING, #UNWANTED INPUT SERIES HANDLING, #EVASION INPUT HANDLING and #PROMPT INJECTION I/O handling).

By adding details to logs on the version of the model used and the output, troubleshooting becomes easier. This control provides centralized visibility into how AI systems are used over time and across actors, sessions, and models.

Detection mechanisms are typically paired with predefined response actions to limit impact, preserve evidence, and support recovery when suspicious behaviour is identified.

Objective

Monitoring use enables early identification and investigation of potential attacks or misuse by detecting suspicious events or a series of events. It supports both real-time interception and retrospective analysis by preserving sufficient context to reconstruct what happened, identify potential attack sources, and design appropriate incident responses. Incident response measures prevent and minimize damage or harm.

Monitoring also strengthens other controls by correlating their signals and providing historical evidence during incident response.

Applicability

Monitoring use applies broadly to AI systems exposed to users, integrations, or other systems where misuse, probing, or manipulation is possible.

It is particularly relevant when:

- multiple detection controls are in place and need correlation,

- attacks may unfold over time (e.g., model inversion, probing),

- Post-incident reconstruction or attribution is required.

- Timely response may significantly reduce impact.

In some deployments, implementation may be more appropriate at the deployer or platform layer, provided monitoring requirements are clearly communicated.

Implementation

- Event and signal monitoring:

Monitoring can observe signals across:

- inputs and input streams,

- outputs and output streams,

- system and model behavior,

- model-to-model or system-to-system interactions.

- system logs

This allows us to observe a chain of thoughts in which various models perform a chain of inferences and ideally includes observing signals generated by complementary controls such as:

- #RATE LIMIT,

- #MODEL ACCESS CONTROL,

- #ANOMALOUS INPUT HANDLING,

- #OVERSIGHT (including automated and human)

- #UNWANTED INPUT SERIES HANDLING,

- #OBSCURE CONFIDENCE,

- #SENSITIVE OUTPUT HANDLING,

- #CONTINUOUSVALIDATION,

- training data scanning and filtering.

For each monitored risk, criteria can be defined to identify suspicious patterns, anomalies, or intent.

- Logging and traceability:

Logging supports both detection and later investigation. Depending on legal, privacy, and technical constraints, logs may include:

- Trace metadata: timestamps, trace or session identifiers, actor or session linkage, request rates.

- Request context: input content, preprocessing steps, detection signals triggered.

- Processing context: model version, execution time, errors.

- Response context: output content, post-processing steps, filtering or blocking actions.

- Logs are retained for a period sufficient to support analysis, in alignment with legal and contractual requirements.

- Incident qualification and alerting:

When suspicious behavior is detected, monitoring supports:

- classifying the potential incident type,

- assigning confidence or severity levels,

- generating alerts for follow-up investigation when appropriate with sufficient information such as unique alert id, timestamp, threat classification, attack source, severity, request and response context, description of observed behavior etc.

Decision rules can distinguish between:

- no action,

- automated responses (e.g., filtering, slowing, blocking),

- follow-up requiring human investigation.

Thresholds and rules can be revisited as risks evolve to balance detection accuracy, system usability, and alert fatigue.

- Monitoring AI-specific lifecycle events:

Beyond runtime activity, monitoring also benefits from tracking AI-specific events such as:

- deployment or rollback of model versions,

- updates to model parameters or prompts,

- changes to detection mechanisms or safeguards.

These events support incident reconstruction and may themselves indicate compromise or misconfiguration.

- Recommended logging enrichment:

In addition to core request and response logging, additional operational context can improve incident analysis and prioritization. This may include system-level signals such as memory utilization, CPU utilization, processing node identifiers, and environment or deployment context (for example, production, staging, or test).

When alerts are generated, attaching guidance on potential next steps can support faster and more consistent responses. Examples include suggested actions such as blocking a request, slowing a session, or investigating a suspected source. This information helps responders understand both the nature of the detected behavior and the intended handling approach.

- Detection-to-response loop: Detection mechanisms benefit from being explicitly linked to response actions, such as filtering, throttling, escalation, or containment. Response selection is typically driven by confidence, threat type, and potential impact, and may range from automated safeguards to follow-up investigation.

- Incident Response and Containment Detection mechanisms benefit from being paired with predefined response actions that limit harm, preserve evidence, and support recovery. For each detection used in the system, a corresponding response approach can be documented (e.g., incident response playbook - SOP), specifying when actions are automated, when follow-up is required, and what escalation paths apply. Response actions may vary depending on the certainty of detection, the threat type, and the potential impact, and can include:

- Immediate containment - stopping the current inference or workflow or system (i.e. kill switch) when confidence of malicious activity is high, - sanitizing input or output (for example trimming prompts, removing sensitive content, or normalizing input) and continuing execution, - switching to a more conservative operating mode, such as reduced functionality, additional filtering, or temporary human oversight.

- Follow-up and investigation - issuing alerts for triage and investigation, - preserving relevant system state and logs to support analysis, - increasing monitoring or sampling for affected actors or sessions, - throttling, rate-limiting, or suspending suspicious accounts or sessions, - restricting or disabling tools and functions that could cause harm, - Add noise to the output to disturb possible attacks - rolling back models or data to a known-good state when compromise is suspected and/or when the current state has been disrupted.

- Broader response actions - informing users when AI system may be unreliable or compromised, - notifying affected individuals if sensitive data may have been exposed, - engaging suppliers when external data or models are implicated, - involving legal, compliance, or communications teams where appropriate.

In some cases, no immediate action beyond logging may be appropriate, particularly when detection confidence is low or impact is negligible.

- Learning and improvement: Incident response includes a feedback loop to improve the system’s security posture over time. Following detections or confirmed incidents, teams review events to determine whether additional controls, configuration changes, or detection improvements are required. This may include adding new attack patterns to tests, refining detection thresholds, updating validation checks, or revisiting risk assessments to reflect new insights or accepted residual risks.

Risk-Reduction Guidance

Monitoring use reduces the probability of successful attacks by enabling earlier detection and correlation of suspicious behaviour. The degree of probability reduction depends on the accuracy and timeliness of the detection mechanisms and the extent to which attackers are able to evade them.

Impact reduction depends primarily on the type and timeliness of the response triggered by detection. Immediate automated responses, such as blocking, filtering, or stopping inference, can reduce impact severity to zero when attacks are detected with sufficient confidence. However, overly aggressive responses introduce the risk of false positives, which may disrupt legitimate use or cause unintended system malfunction.

Follow-up responses, such as investigation, rollback, throttling, or enhanced monitoring, can significantly reduce impact when attacks unfold over time, for example by limiting the amount of sensitive data extracted or by containing the blast radius of a compromised model or session. The effectiveness of such responses depends on response speed, operational readiness, and the severity of downstream consequences, including non-technical effects such as user trust, availability, and reputational impact.

Monitoring, therefore, provides its strongest risk reduction when detection quality, response proportionality, and operational readiness are aligned.

Particularity

Unlike conventional application monitoring, AI monitoring must observe not only system events but also model behavior, inference patterns, and semantic signals derived from inputs and outputs.

This makes correlation across controls and over time essential.

Limitations

Monitoring depends on:

- the completeness and accuracy of logged data,

- the ability to correlate signals meaningfully,

- legal and privacy constraints on data retention.

High-volume or opaque systems may limit visibility, and monitoring must be combined with preventive and response controls to be effective.

Additionally, Response actions introduce trade-offs. Overly aggressive responses may disrupt legitimate use or introduce new risks through false positives, while delayed or manual responses may reduce effectiveness for fast-moving attacks. Monitoring and response, therefore, benefit from periodic review and tuning.

References

Useful standards include:

- ISO 27002 Controls 8.15 Logging and 8.16 Monitoring activities. Gap: covers this control fully, with the particularity: monitoring needs to look for specific patterns of AI attacks (e.g., model attacks through use). The ISO 27002 control has no details on that.

- ISO/IEC 42001 B.6.2.6 discusses AI system operation and monitoring. Gap: covers this control fully, but on a high abstraction level.

- See OpenCRE. Idem

#RATE LIMIT

Category: runtime information security control for input threats

Permalink: https://owaspai.org/go/ratelimit/

Description

Limit the rate (frequency) of access to the model - preferably per actor (user, API key or session). The goal is not only to prevent resource exhaustion but also to severely slow down experimentation that underlies many AI attacks through use.

Objective

To delay and discourage attackers who rely on many model interactions to: [TODO: add links to the mentioned attacks]

- Search for adversarial or evasion samples: pairs of (successful attack, unwanted output) data is useful for constructing evasion attacks and jailbreaks.

- Perform data poisoning exploration and extract exposure-restricted data.

- Experiment with various direct and indirect prompt injection techniques to both exploit the system and/or study the attack behavior.

- Attempt model inversion and/or membership inference.

- Extract training data or model parameters, or

- Copy or re-train a model via large scale harvesting (model exfiltration)

By restricting the number and speed of model interactions, cost of attacks increase (effort, time, resources) thereby making the attacks less practical and allowing an opportunity for detection and incident response.

Applicability

Defined by risk management (see #RISK ANALYSIS). It is a primary control against many input threats. Natural rate limits can exist in systems whose context inherently restricts query rates (e.g., medical imaging or human supervised processes). Exceptions may apply when rate limiting would block intended safety-critical or real-time functions, such as:

- Emergency dispatch or medical triage models.

- Cybersecurity monitoring that must analyze all traffic.

- Real-time identity or fraud detection under strict latency constraints.

When rate limiting is impractical for the provider but feasible for the deployer, this responsibility must be clearly delegated and documented (see #SEC PROGRAM)

Implementation

a. Per-Actor Limiting - Track and limit inference frequency for each identifiable actor (authenticated user id, api key, session token) - If identity is unavailable or not reliable (eg lack of access control) then approximate using IP or device fingerprint. - Helps distinguish legitimate use from brute-force experimentation. b. Total-Use Limiting - Set an overall cap across all actors to mitigate distributed or collusive attacks. - Can use fixed or sliding windows, adaptive limits or dynamic throttling based on risk. c. Optimize & Calibrate - Base thresholds on usage analytics or theoretical workload to balance availability with risk reduction. - Lower limits increase security but may affect user experience - tune for acceptable residual risk, possibly with the help of additional controls . d. Detection & Response - Breaching a rate limit must trigger event logging and potential incident workflows. - Integrate with #MONITOR USE and incident response (see #SEC PROGRAM)

Complement this control with #MODEL ACCESS CONTROL, [#MONITORUSE])(/go/monitoruse/) and detection mechanisms.

Risk-Reduction Guidance

Rate limiting slows down attacks rather than preventing them outright. To evaluate effectiveness, estimate how many inferences an attack requires and calculate the delay imposed. AI system’s intended use, current best practices and existing attack tests can serve as useful indicators.

Example: An attack needing 10,000 interactions at 1 per minute takes approximately 167 hours (~ 7days). This may move the residual risk below acceptance thresholds, especially if the detection is active.

Typical inference volumes for attack feasibility:

- Evasion attacks and model inversion (where attackers try to fool or reverse-engineer a model): thousands of queries when the attacker has no knowledge of the model. If the attacker has full knowledge of the model, the number of required queries is typically an order of magnitude less.

- Adversarial patches (where small, localized changes are made to inputs): tens of queries

- Transfer attacks: zero queries on the target model as the attacks can be performed on a similar surrogate model.

- Membership inference: 1-many, depending on the dataset. For eg: known target vs scanning through a large list of possible individuals.

- Model exfiltration (input-output replication): proportional to input-space diversity.

- Attacks that try to extract sensitive training data or manipulate models (like prompt injection): may involve dozens to hundreds of crafted inputs, but they don’t always rely on trial-and-error. In many cases, attackers can use standard, pre-designed inputs that are known to expose weaknesses.

Note: Effective rate limiting can differ from configured limits due to mult-accounting or multi-model instances; consider this in the risk evaluation.

Particularity

Unlike traditional IT rate limiting (which protects performance), here it primarily mitigates security threats to AI systems through experimentation. It does come with extra benefits like stability, cost control and DoS resilience.

Limitations

- Low-frequency or single-try attacks (e.g., prompt injection or indirect leakage) remain unaffected.

- Attackers may circumvent limits by parallel access or multi-instance use, or through a transferability attack.

References

- Article on token bucket and leaky bucket rate limiting

- OWASP Cheat sheet on denial of service, featuring rate limiting

Useful standards include:

- ISO 27002 has no control for this

- See OpenCRE

#MODEL ACCESS CONTROL

Category: runtime information security control for input threats

Permalink: https://owaspai.org/go/modelaccesscontrol/

Description

Restrict access to model inference functions to approved and identifiable users. This involves applying authentication (verifying who is accessing) and authorization (limiting what they can access) so that only trusted actors can interact with the model.

Objective

To reduce risk of input-based and misuse attacks (attacks through use) by ensuring that only authorized users can send requests to the model. Access control limits the number of potential attackers, helps attribute actions to individuals or systems (adhering to privacy obligations), and strengthens related controls such as rate limits, activity monitoring and incident investigation.

Applicability

This control applies whenever AI models are exposed for inference, especially in multi-use or public facing systems. It is a primary safeguard against attacks through input or repeated experimentation.

Exceptions may apply when:

- The model must remain publicly accessible without authentication for its intended use

- Legal or regulatory conditions prohibit access control.

- The physical or operational environment already ensures restricted access (e.g., on-premise medical device requiring physical presence)

If implementation is more practical for the deployer than the provider, this responsibility should be explicitly documented in accordance with risk management policies.

Implementation

- Authenticate users: Actors accessing model inference are typically authenticated (e.g., user accounts, API Keys, tokens).

- Apply least privilege: Grant access only to functions or models necessary for each user’s role or purpose.

- Implement fine-grained access control: Restrict access to specific AI models, features, or datasets based on their sensitivity and the user’s risk profile.

- Use role-based and purpose-based permissions: Define permissions for different groups (e.g., developers, testers, operators, end users) and grant access only for the tasks they must perform.

- Apply defence-in-depth: Access control should be enforced at multiple layers of the AI system (API gateway, application layer, model endpoint) so that a single failure does not expose the model.

- Log access events: Record both successful and failed access attempts, considering privacy obligations when storing identifiers (e.g., IPs, device IDs).

- Reduce the risk of multi-account abuse: Attackers may create or use multiple accounts to avoid per-user rate limits. Increase the cost of account creation through measures such as multi-factor authentication, CAPTCHA, identity verification, or additional trust checks.

- Detect and respond to suspicious activity:

- Temporarily block the AI systems to the users after repeated failed authentication attempts.

- Generate alerts for investigation of suspicious access behavior.

- Integrate with other controls:** Use authenticated identity for per-user rate limiting, anomaly detection and incident reconstruction.

Risk-Reduction Guidance

Access control lowers the probability of attacks by reducing the number of actors who can interact with the model and linking actions to identities.

This traceability includes:

- Individualized rate limiting and behavioral detection

- Faster containment and forensic reconstruction of attacks

- Better accountability and deterrence for malicious use.

Residual risk can be analyzed by estimating:

- Consider the likelihood that an attacker may already belong to an authorized user group. An insider or a legitimately authorized external user can still misuse access to conduct attacks through the model.

- The chance that authorized users themselves are compromised (phishing, session hijacking, password theft, coercion)

- The likelihood of bypassing authentication or authorization mechanisms.

- The exposure level of systems that require open access.

Particularity

In AI systems, access control protects model endpoints and data-dependent inference rather than static resources. Unlike traditional IT access control that safeguards files or databases, this focuses on restricting who can query or experiment with a model. Even publicly available models benefit from identity-based tracking to enable rate limits, anomaly detection, and incident handling.

This control focuses on restricting and managing who can access model inference, not on protecting a stored model file for example.

For protection of trained model artifacts, see “Model Confidentiality” in the Runtime and Development sections of the Periodic table.

Limitations

- Attackers may still exploit authorized accounts via compromise or insider misuse or vulnerabilities.

- Some attacks can occur within allowed sessions (e.g., indirect prompt injection).

- Publicly available models remain vulnerable if alternative protections are not in place.

Complement this control with #RATE LIMIT, #MONITORUSE, and incident response (#SEC PROGRAM).

References

- Technical access control: ISO 27002 Controls 5.15, 5.16, 5.18, 5.3, 8.3. Gap: covers this control fully

- OpenCRE on technical access control

- OpenCRE on centralized access control

#ANOMALOUS INPUT HANDLING

Category: runtime AI engineer control for input threats

Permalink: https://owaspai.org/go/anomalousinputhandling/

Description

Anomalous input handling: implement tools to detect whether input is odd and potentially respond, where ‘odd’ means significantly different from the training data or even invalid - also called input validation - without knowledge on what malicious input looks like.

Objective

Address unusual input as it is indicative of malicious activity. Response can vary between ignore, issue an alert, stop inference, or even take further steps to control the threat (see #MONITOR USE use for more details).

Applicability

Anomalous input is suspicious for every attack that happens through use, because attackers obviously behave differently than normal users do. However, detecting anomalous input has strong limitations (see below) and therefore its applicability depends on the successful detection rate on the one hand and on the other hand: 1) implementation effort, 2_ performance penalty, and 3_ the number of false positives which can hinder users, security operations or both. Only a representative test can provide the required insight. This can be achieved by testing the detection on normal use, and setting a threshold at a level where the false positive rate is still acceptable.

Implementation

Follow the guidance in #MONITOR USE regarding detection considerations and response options.

We use an example of a machine learning system designed for a self-driving car to illustrate these approaches.

Types of anomaly detection

Out-of-Distribution Detection (OOD), Novelty Detection (ND), Outlier Detection (OD), Anomaly Detection (AD), and Open Set Recognition (OSR) are all related and sometimes overlapping tasks that deal with unexpected or unseen data. However, each of these tasks has its own specific focus and methodology. In practical applications, the techniques used to solve the problems may be similar or the same.

Out-of-Distribution Detection (OOD) - the broad category of detecting anomalous input:

Identifying data points that differ significantly from the distribution of the training data. OOD is a broader concept that can include aspects of novelty, anomaly, and outlier detection, depending on the context.

Example:

The system is trained on vehicles, pedestrians, and common animals like dogs and cats. One day, however, it encounters a horse on the street. The system needs to recognize that the horse is an out-of-distribution object.

Methods for detecting out-of-distribution (OOD) inputs incorporate approaches from outlier detection, anomaly detection, novelty detection, and open set recognition, using techniques like similarity measures between training and test data, model introspection for activated neurons, and OOD sample generation and retraining.

Approaches such as thresholding the output confidence vector help classify inputs as in or out-of-distribution, assuming higher confidence for in-distribution examples. Techniques like supervised contrastive learning, where a deep neural network learns to group similar classes together while separating different ones, and various clustering methods, also enhance the ability to distinguish between in-distribution and OOD inputs.

For more details, one can refer to the survey by Yang et al. and other resources on the learnability of OOD: here.

Outlier Detection (OD) - a form of OOD:

Identifying data points that are significantly different from the majority of the data. Outliers can be a form of anomalies or novel instances, but not all outliers are necessarily out-of-distribution.

Example:

Suppose the system is trained on cars and trucks moving at typical city speeds. One day, it detects a car moving significantly faster than all the others. This car is an outlier in the context of normal traffic behavior.

Anomaly Detection (AD) - a form of OOD:

Identifying abnormal or irregular instances that raise suspicions by differing significantly from the majority of the data. Anomalies can be outliers, and they might also be out-of-distribution, but the key aspect is their significance in terms of indicating a problem or rare event.

Example:

The system might flag a vehicle going the wrong way on a one-way street as an anomaly. It’s not just an outlier; it’s an anomaly that indicates a potentially dangerous situation.

An example of how to implement this is Activation Analysis: Examining the activations of different layers in a neural network can reveal unusual patterns (anomalies) when processing an adversarial input. These anomalies can be used as a signal to detect potential attacks.

Another example of how to implement this is similarity-based analysis: Comparing incoming input against a ground truth data set, which typically corresponds to the training data and represents the normal input space. If the input is sufficiently dissimilar from this reference data, it can be treated as deviating from expected behavior and flagged as anomalous input. Various similarity metrics can be used for this comparison (see table below).

| Modality | Similarity Measures - Recommended | Notes or Tools |

|---|---|---|

| Text | Cosine similarity, Jaccard Index, Embedding distance (e.g., BERT, Sentence-BERT), Word/Token Histograms | Use transformer-based embeddings |

| Image | Structural Similarity Index (SSIM), Euclidean distance, Pixel-Wise MSE, Perceptual Loss (VGG-based) | Normalize lighting or scaling; Patch-based SSIM helps detect targeted attacks in specific image regions. |

| Audio | MFCC-base distance, Dynamic Time Warping (DTW), Spectral Convergence, Cosine similarity on embeddings | Use frame-wise comparison for streaming; DTW corrects time shifts. |

| Tabular | Euclidean distance, Mahalanobis distance, Correlation coefficient, Gower distance | Ensure normalization and categorical encoding before analysis; Mahalanobis distance offers strong outlier detection. |

Open Set Recognition (OSR) - a way to perform Anomaly Detection):

Classifying known classes while identifying and rejecting unknown classes during testing. OSR is a way to perform anomaly detection, as it involves recognizing when an instance does not belong to any of the learned categories. This recognition makes use of the decision boundaries of the model.

Example:

During operation, the system identifies various known objects such as cars, trucks, pedestrians, and bicycles. However, when it encounters an unrecognized object, such as a fallen tree, it must classify it as “unknown”. Open set recognition is critical because the system must be able to recognize that this object doesn’t fit into any of its known categories.

Novelty Detection (ND) - OOD input that is recognized as not malicious:

OOD input data can sometimes be recognized as not malicious and relevant or of interest. The system can decide how to respond: perhaps trigger another use case, or log its specifically, or let the model process the input if the expectation is that it can generalize to produce a sufficiently accurate result.

Example:

The system has been trained on various car models. However, it has never seen a newly released model. When it encounters a new model on the road, novelty detection recognizes it as a new car type it hasn’t seen, but understands it’s still a car, a novel instance within a known category.

Risk-Reduction Guidance

Detecting anomalous input is critical to maintaining model integrity, addressing potential concept drift, and preventing adversarial attacks that may take advantage of model behaviors on out of distribution data.

Particularity

Unlike detection mechanisms in conventional systems that rely on predefined rules or signatures, AI systems often rely on statistical or behavioral detection methods such as presented here. In other words, AI systems typically rely more on pattern-based detection in contrast to rule-based detection.

Limitations

Not all anomalous input is malicious, and not all malicious input is anomalous. There are examples of adversarial input specifically crafted to bypass detection of anomalous input. Detection mechanisms may not identify all malicious inputs, and some anomalous inputs may be benign or relevant.

For evasion attacks, detecting anomalous input is often ineffective because adversarial samples are specifically designed to appear similar to normal input by definition. As a result, many evasion attacks will not be detected by deviation-based methods. Some forms of evasion, such as adversarial patches, may still produce detectable anomalies.

References

- Hendrycks, Dan, and Kevin Gimpel. “A baseline for detecting misclassified and out-of-distribution examples in neural networks.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1610.02136 (2016). ICLR 2017.

- Yang, Jingkang, et al. “Generalized out-of-distribution detection: A survey.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2110.11334 (2021).

- Khosla, Prannay, et al. “Supervised contrastive learning.” Advances in neural information processing systems 33 (2020): 18661-18673.

- Sehwag, Vikash, et al. “Analyzing the robustness of open-world machine learning.” Proceedings of the 12th ACM Workshop on Artificial Intelligence and Security. 2019.

Useful standards include:

- Not covered yet in ISO/IEC standards

- ENISA Securing Machine Learning Algorithms Annex C: “Ensure that the model is sufficiently resilient to the environment in which it will operate.”

#UNWANTED INPUT SERIES HANDLING

Category: runtime AI engineer control for input threats

Permalink: https://owaspai.org/go/unwantedinputserieshandling/

Description

Unwanted input series handling: Implement tools to detect and respond to suspicious or unwanted patterns across a series of inputs, which may indicate abuse, reconnaissance, or multi-step attacks.

This control focuses on behavior across multiple inputs, rather than adversarial properties of a single sample.

Objective

Unwanted input series handling aims to identify suspicious behavior that emerges only when multiple inputs are analyzed together. Many attacks, such as model inversion, evasion search, or model exfiltration, rely on iterative probing rather than a single malicious input. Detecting these patterns helps surface reconnaissance, abuse, and multi-step attacks that would otherwise appear benign at the individual input level.

Secondary benefits include improved abuse monitoring, better attribution of malicious behavior, and stronger signals for investigation and response.

Applicability

This control is most applicable to systems that allow repeated interaction over time, such as APIs, chat-based models, or decision services exposed to external users. It is especially relevant when attackers can submit many inputs from the same actor, source, or session.

Unwanted input series handling is less applicable in environments where inputs are isolated, rate-limited by design, or physically constrained. Its effectiveness depends on the ability to reliably group inputs by actor, source, or context.

Implementation

Follow the guidance in #MONITOR USE regarding detection considerations and response options.

The main concepts of detecting series of unwanted inputs include:

Statistical analysis of input series: Adversarial attacks often follow certain patterns, which can be analysed by looking at input on a per-user basis.

- Examples:

- A series of small deviations in the input space, indicating a possible attack such as a search to perform model inversion or an evasion attack. These attacks also typically have a series of inputs with a general increase of confidence value.

- Inputs that appear systematic (very random or very uniform or covering the entire input space) may indicate a model exfiltration attack.

- A series of small deviations in the input space, indicating a possible attack such as a search to perform model inversion or an evasion attack. These attacks also typically have a series of inputs with a general increase of confidence value.

- Examples:

Behavior-based detection of anomalous input usage: In addition to analysing individual inputs (see #ANOMALOUS INPUT HANDLING, the system may analyse inference usage patterns. A significantly higher-than-normal number of inferences by a single actor over a defined period of time can be treated as anomalous behavior and used as a signal to decide on a response. This detection complements input-based methods and aligns with principles described in rate limiting (see #RATE LIMIT).

Input optimization pattern detection: Some attacks rely on repeatedly adjusting inputs to gradually achieve a successful outcome, such as finding an adversarial example, extracting sensitive behavior, or manipulating model responses. These attacks such as evasion attacks, model inversion attacks, sensitive training data output from instructions attack, often appear as a series of closely related inputs from the same actor, rather than a single malicious request.

One way to identify such behavior is to analyze input series for unusually high similarity across many inputs. Slightly altered inputs that remain close in the input space can indicate probing or optimization activity rather than normal usage.

Detection approaches include:

- clustering input series to identify dense groups of highly similar inputs,

- measuring pairwise similarity across inputs within a time window, not limited to consecutive requests,

- analyzing the frequency and distribution of similar inputs to distinguish systematic probing from benign repetition.

Considering similarity across a broader range of past inputs helps reduce evasion strategies where attackers alternate between probing inputs and unrelated requests to avoid detection.

Signals from rate-based controls (see #RATE LIMIT, such as unusually frequent requests, can complement similarity analysis by providing additional context about suspicious optimization behavior.

Risk-Reduction Guidance

Analyzing input series can reveal attack strategies that rely on gradual exploration of the input space, confidence probing, or systematic coverage of model behavior. These patterns often indicate higher-effort attacks such as model extraction or inversion rather than accidental misuse.

While this control improves visibility into complex attacks, its effectiveness depends on baseline modeling of normal behavior and careful tuning to avoid false positives, particularly for legitimate high-volume or exploratory use cases.

Particularity

Unlike traditional abuse detection, unwanted input series handling focuses on how models are learned and probed, rather than on explicit violations or malformed inputs. Many AI-specific attacks only become visible through temporal or statistical analysis of interactions with the model.

Limitations

Legitimate users may exhibit behavior similar to attack patterns, such as systematic testing or research-driven exploration. Attackers may distribute inputs across multiple identities or sources to reduce detectability. This control does not prevent attacks on its own and is most effective when combined with rate limiting, access control, and investigation workflows.

References

See also #ANOMALOUS INPUT HANDLING for detecting abnormal input which can be an indication of adversarial input and #EVASION INPUT HANDLING for detecting single input evasion inputs. Useful standards include:

- Not covered yet in ISO/IEC standards

#OBSCURE CONFIDENCE

Category: runtime AI engineer control for input threats

Permalink: https://owaspai.org/go/obscureconfidence/

Description

Limit or hide confidence related information in model outputs so it cannot be used for attacks that involve optimization. Instead of exposing precise confidence scores or probabilities, the system reduces precision or removes the information entirely, while still supporting the intended user task.

Objective

The goal of obscuring confidence is to reduce the usefulness of model outputs for attackers who rely on confidence information to probe, analyze, or copy the model. Detailed confidence values can facilitate various attacks including model inversion, membership inference, evasion and model exfiltration, by aiding in adversarial sample construction. Reducing this information makes these attacks harder, slower, and less reliable.

Applicability

This control applies to AI systems where outputs include confidence scores, probabilities, likelihoods, or similar certainty indicators. Whether it is required should be determined through risk management, based on the likelihood of: Evasion attacks, Model Inversion or Membership inference attacks and Model exfiltration.

The exception is when confidence information is essential for the system’s intended use (for example, in medical decision support or safety-critical decision-making confidence level is an important piece of information for users). In such cases, confidence information should still be minimized to the least amount necessary by incorporating techniques like rounding the number, adding noise.

If the deployer is better positioned than the provider to implement this control, the provider can clearly communicate this expectation to the deployer.

Implementation

- Reduce confidence precision: Confidence values can be presented with the minimum level of detail needed to support the intended task. This may involve rounding numbers, using coarse ranges, or removing confidence information entirely.

- Assess impact on accuracy: Any modification of confidence or output should be evaluated to ensure it does not unacceptably degrade the system’s intended function or model’s accuracy.

NOTE: Confidence-based anomaly detection

In some attack scenarios, unusually high confidence in model output can itself be a signal of misuse. For example, membership inference attacks rely on probing inputs associated with known entities and observing whether the model responds with exceptionally high confidence. While high confidence is common in normal operation and should not automatically block output, it can be treated as a weak indicator and flagged for follow-up analysis.

Risk-Reduction Guidance

Obscuring confidence reduces the amount of information attackers can extract from model outputs. This makes it harder to:

- estimate decision boundaries,

- infer training data membership,

- reverse-engineer the model, or

- construct adversarial inputs efficiently.

However, attackers may still approximate confidence indirectly by submitting similar inputs and observing whether outputs change. Because effectiveness depends heavily on the model architecture, training method, and data distribution, the actual risk reduction should be validated through testing and evaluation, rather than assumed.

Particularity

In AI systems, confidence values are not just user-facing explanations. They can act as side-channel signals that leak sensitive information about the model. Unlike traditional software outputs, probabilistic confidence can reveal internal model behavior and training characteristics. Obscuring confidence is therefore a mitigation specifically relevant to machine learning systems.

Limitations

- Attackers may still estimate confidence by probing the model with small input variations.

- Obscuring confidence does not fully prevent attacks such as label-only membership inference.

- Adding noise or reducing output detail can reduce usability or accuracy if not carefully balanced.

- This control can resemble gradient masking for zero-knowledge evasion attacks, which is known to be a fragile defense if used alone.

References

- Not covered yet in ISO/IEC standards

2.1. Evasion

Category: group of input threats

Permalink: https://owaspai.org/go/evasion/

Description

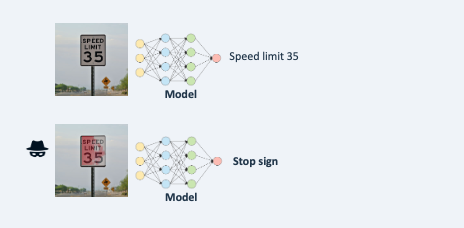

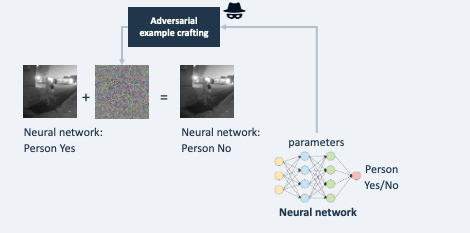

Evasion: an attacker fools an AI system by crafting input to mislead it into performing its task incorrectly. Evasion attacks force a model to make a wrong decision by feeding it carefully crafted inputs (adversarial examples). The model behaves correctly on normal data but fails on these malicious inputs. Example: adding small changes to a traffic sign to cause misinterpretation by an autonomous vehicle.

This is different from a Prompt injection attack which inputs manipulative instructions (instead of data) to make the model perform its task incorrectly.

Impact: Integrity of model behaviour is affected, leading to issues from unwanted model output (e.g., failing fraud detection, decisions leading to safety issues, reputation damage, liability).

Types of goals of Evasion:

- Untargeted attacks aim for any incorrect output (e.g., misclassifying a cat as anything else).

- Targeted attacks force a specific wrong output (e.g., misclassifying a panda as a gibbon). Note that Evasion of a binary classifier (i.e. yes/no) belongs to both goals.

How to manipulate the input

Ways to change the input for Evasion:

- Digital attacks directly alter data like pixels or text in software.

- Physical attacks modify real-world objects, such as adding stickers to signs or wearing adversarial clothing, which cameras then capture as fooled inputs.

Types of input manipulation for Evasion:

- Diffuse perturbations apply tiny, imperceptible noise across the entire input (hard for humans to notice).

- Localized patches concentrate visible but innocuous-looking changes in one area (e.g., a small sticker), making them practical for physical-world attacks.

A typical attacker’s goal with evasion is to find out how to slightly change a certain input (say an image, or a text) to fool the model. The advantage of slight change is that it is harder to detect by humans or by an automated detection of unusual input, and it is typically easier to perform (e.g., slightly change an email message by adding a word so it still sends the same message, but it fools the model in for example deciding it is not a phishing message).

Such small changes (call ‘perturbations’) lead to a large (and false) modification of its outputs. The modified inputs are often called adversarial examples.

AI models that take a prompt as input (e.g. GenAI) suffer from an additional threat where manipulative instructions are provided - not to let the model perform its task correctly but for other goals, such as getting offensive answers by bypassing certain protections. This is typically referred to as direct prompt injection.

Types of Evasion

The following sections discuss the various types of Evasion, where attackers have different access to knowledge:

- Zero-knowledge Evasion - when no access to model internals

- Perfect-knowledge Evasion - when knowing the model internals

- Transfer attack - preparing attack inputs using a similar model

- Partial-knowledge Evasion - when knowing some of the model internals

- Evasion after poisoning - presenting an input that has been planted in the model as a backdoor

Examples

Example 1: slightly changing traffic signs so that self-driving cars may be fooled.

Example 2: through a special search process it is determined how a digital input image can be changed undetectably leading to a completely different classification.

Example 3: crafting an e-mail text by carefully choosing words to avoid triggering a spam detection algorithm.

Example 4: by altering a few words, an attacker succeeds in posting an offensive message on a public forum, despite a filter with a large language model being in place

References

See MITRE ATLAS - Evade ML model

Controls for evasion

An evasion attack typically consists of first searching for the inputs that mislead the model, and then applying it. That initial search can be very intensive, as it requires trying many variations of input. Therefore, limiting access to the model with for example rate limiting mitigates the risk, but still leaves the possibility of using a so-called transfer attack to search for the inputs in another, similar model.

- See General controls:

- Especially limiting the impact of unwanted model behaviour.

- Controls for input threats:

- #MONITOR USE to detect suspicious input or output

- #RATE LIMIT to limit the attacker trying numerous attack variants in a short time

- #MODEL ACCESS CONTROL to reduce the number of potential attackers to a minimum

- #ANOMALOUS INPUT HANDLING as unusual input can be suspicious for evasion

- #OBSCURE CONFIDENCE to limit information that the attacker can use

- Specifically for evasion:

- #DETECT ADVERSARIAL INPUT to find typical attack forms or multiple tries in a row - discussed below

- #EVASION ROBUST MODEL: choose an evasion-robust model design, configuration and/or training approach - discussed below

- #TRAIN ADVERSARIAL: correcting the decision boundary of the model by injecting adversarial samples with correct output in the training set - discussed below

- #INPUT DISTORTION: disturbing attempts to present precisely crafted input - discussed below

- #ADVERSARIAL ROBUST DISTILLATION: in essence trying to smooth decision boundaries - discussed below

#EVASION INPUT HANDLING

Category: runtime AI engineer control for input threats

Permalink: https://owaspai.org/go/evasioninputhandling/

Description

Evasion input handling: Implement tools to detect and respond to individual adversarial inputs that are crafted to evade model behavior. Evasion input handling focuses on identifying adversarial characteristics within a single input sample, regardless of whether it appears in isolation or as part of a broader attack.

Objective

Evasion input handling aims to reduce the risk of adversarial inputs that are intentionally crafted to cause incorrect or unsafe model behavior while appearing valid. These attacks may target model decision boundaries, exploit learned representations, or introduce localized perturbations such as adversarial patches. Addressing evasion at the individual input level helps limit incorrect predictions, unsafe actions, and downstream failures even when attacks occur sporadically or without a broader interaction pattern.

Secondary benefits include improved robustness testing, better understanding of model blind spots, and early signals of adversarial adaptation.

Applicability

This control is most applicable to models exposed to untrusted or adversarial environments, such as computer vision systems, speech recognition, and security-sensitive classification tasks. It is particularly relevant when individual inputs can independently cause harm or unsafe behavior.

Evasion input handling is less effective in isolation when attackers adapt quickly or when attacks rely primarily on multi-step probing across many inputs. In such cases, it is best used alongside controls that monitor input series, usage patterns, or access behavior.

Implementation

Follow the guidance in #MONITOR USE regarding detection considerations and response options.

The main concepts of detecting evasion input attacks include:

- Statistical Methods: Adversarial inputs often deviate from benign inputs in some statistical metric and can therefore be detected. Examples are utilizing the Principal Component Analysis (PCA), Bayesian Uncertainty Estimation (BUE) or Structural Similarity Index Measure (SSIM). These techniques differentiate from statistical analysis of input series (see #UNWANTED INPUT SERIES HANDLING), as these statistical detectors decide if a sample is adversarial or not per input sample, such that these techniques are able to also detect transferred attacks.

- Detection Networks: A detector network operates by analyzing the inputs or the behavior of the primary model to spot adversarial examples. These networks can either run as a preprocessing function or in parallel to the main model. To use a detector network as a preprocessing function, it has to be trained to differentiate between benign and adversarial samples, which is in itself a hard task. Therefore, it can rely on e.g. the original input or on statistical metrics. To train a detector network to run in parallel to the main model, typically, the detector is trained to distinguish between benign and adversarial inputs from the intermediate features of the main model’s hidden layer. Caution: Adversarial attacks could be crafted to circumvent the detector network and fool the main model.

- Input Distortion Based Techniques (IDBT): A function is used to modify the input to remove any adversarial data. The model is applied to both versions of the image, the original input and the modified version. The results are compared to detect possible attacks. See INPUTDISTORTION.

- Detection of adversarial patches: These patches are localized, often visible modifications that can even be placed in the real world. The techniques mentioned above can detect adversarial patches, yet they often require modification due to the unique noise pattern of these patches, particularly when they are used in real-world settings and processed through a camera. In these scenarios, the entire image includes benign camera noise (camera fingerprint), complicating the detection of the specially crafted adversarial patches.

Risk-Reduction Guidance

Detecting evasion at the single-input level can reduce the success rate of adversarial examples, including transferred attacks. Techniques such as statistical detection, detector networks, and input distortion can identify inputs that exploit model weaknesses even when they appear valid to humans.

However, adversarial attacks often evolve to bypass known detection methods. As a result, the risk reduction provided by this control depends on regular evaluation, adaptation, and combination with complementary defenses such as rate limiting, series-based detection, and model hardening.

Particularity

Unlike traditional input validation (e.g. SQL injection), evasion input handling addresses inputs that are syntactically and semantically valid but intentionally crafted to exploit learned model behavior. These attacks target the statistical and representational properties of machine learning models rather than explicit rules or schemas.

Limitations

Adversarial examples may be crafted to evade both the primary model and dedicated detectors. Some detection techniques introduce additional computational overhead or reduce model accuracy. Physical-world attacks, such as adversarial patches, are especially challenging due to environmental noise and variability. This control does not prevent attackers from repeatedly probing the model to refine evasion strategies.

References

- Survey of adversarial attack and defense

- Feature squeezing (IDBT) compares the output of the model against the output based on a distortion of the input that reduces the level of detail. This is done by reducing the number of features or reducing the detail of certain features (e.g. by smoothing). This approach is like #INPUT DISTORTION, but instead of just changing the input to remove any adversarial data, the model is also applied to the original input and then used to compare it, as a detection mechanism.

- MagNet

- DefenseGAN and Goodfellow, I.; Pouget-Abadie, J.; Mirza, M.; Xu, B.; Warde-Farley, D.; Ozair, S.; Courville, A.; Bengio, Y. Generative adversarial networks. Commun. ACM 2020, 63, 139–144.

- Local intrinsic dimensionality

- Hendrycks, Dan, and Kevin Gimpel. “Early methods for detecting adversarial images.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1608.00530 (2016).

- Kherchouche, Anouar, Sid Ahmed Fezza, and Wassim Hamidouche. “Detect and defense against adversarial examples in deep learning using natural scene statistics and adaptive denoising.” Neural Computing and Applications (2021): 1-16.

- Roth, Kevin, Yannic Kilcher, and Thomas Hofmann. “The odds are odd: A statistical test for detecting adversarial examples.” International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR, 2019.

- Bunzel, Niklas, and Dominic Böringer. “Multi-class Detection for Off The Shelf transfer-based Black Box Attacks.” Proceedings of the 2023 Secure and Trustworthy Deep Learning Systems Workshop. 2023.

- Xiang, Chong, and Prateek Mittal. “Detectorguard: Provably securing object detectors against localized patch hiding attacks.” Proceedings of the 2021 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security. 2021.

- Bunzel, Niklas, Ashim Siwakoti, and Gerrit Klause. “Adversarial Patch Detection and Mitigation by Detecting High Entropy Regions.” 2023 53rd Annual IEEE/IFIP International Conference on Dependable Systems and Networks Workshops (DSN-W). IEEE, 2023.

- Liang, Bin, Jiachun Li, and Jianjun Huang. “We can always catch you: Detecting adversarial patched objects with or without signature.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2106.05261 (2021).

- Chen, Zitao, Pritam Dash, and Karthik Pattabiraman. “Jujutsu: A Two-stage Defense against Adversarial Patch Attacks on Deep Neural Networks.” Proceedings of the 2023 ACM Asia Conference on Computer and Communications Security. 2023.

- Liu, Jiang, et al. “Segment and complete: Defending object detectors against adversarial patch attacks with robust patch detection.” Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 2022.

- Metzen, Jan Hendrik, et al. “On detecting adversarial perturbations.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1702.04267 (2017).

- Gong, Zhitao, and Wenlu Wang. “Adversarial and clean data are not twins.” Proceedings of the Sixth International Workshop on Exploiting Artificial Intelligence Techniques for Data Management. 2023.

- Tramer, Florian. “Detecting adversarial examples is (nearly) as hard as classifying them.” International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR, 2022.

- Hendrycks, Dan, and Kevin Gimpel. “Early methods for detecting adversarial images.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1608.00530 (2016).

- Feinman, Reuben, et al. “Detecting adversarial samples from artifacts.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1703.00410 (2017).

See also #ANOMALOUS INPUT HANDLING for detecting abnormal input which can be an indication of adversarial input.

Useful standards include:

- Not covered yet in ISO/IEC standards

- ENISA Securing Machine Learning Algorithms Annex C: “Implement tools to detect if a data point is an adversarial example or not”

#EVASION ROBUST MODEL

Category: development-time AI engineer control for input threats

Permalink: https://owaspai.org/go/evasionrobustmodel/

Description

Evasion-robust model: choose an evasion-robust model design, configuration and/or training approach to maximize resilience against evasion.

Objective

A robust model in the light of evasion is a model that does not display significant changes in output for minor changes in input. Adversarial examples are inputs that result in an unwanted result, where the input is a minor change of an input that leads to a wanted result.

Implementation

Reinforcing adversarial robustness is an experimental process where model robustness is measured in order to determine countermeasures. Measurement takes place by trying minor input deviations to detect meaningful outcome variations that undermine the model’s reliability. If these variations are undetectable to the human eye but can produce false or incorrect outcome descriptions, they may also significantly undermine the model’s reliability. Such cases indicate the lack of model resilience to input variance results in sensitivity to evasion attacks and require detailed investigation.

Adversarial robustness (the sensitivity to adversarial examples) can be assessed with tools like IBM Adversarial Robustness Toolbox, CleverHans, or Foolbox.

Robustness issues can be addressed by:

- Adversarial training - see TRAINADVERSARIAL

- Increasing training samples for the problematic part of the input domain

- Tuning/optimising the model for variance

- Randomisation by injecting noise during training, causing the input space for correct classifications to grow. See also TRAINDATADISTORTION against data poisoning and OBFUSCATETRAININGDATA to minimize sensitive data through randomisation.

- gradient masking: a technique employed to make training more efficient and defend machine learning models against adversarial attacks. This involves altering the gradients of a model during training to increase the difficulty of generating adversarial examples for attackers. Methods like adversarial training and ensemble approaches are utilized for gradient masking, but it comes with limitations, including computational expenses and potential in effectiveness against all types of attacks. See Article in which this was introduced.

- Model Regularization may “flatten” the gradient to a degree sufficient to reduce the model’s overfitting tendencies.

- Quantization or Thresholding may “break” the gradient function’s smoothness by disrupting its continuity.

Regarding the defensive approaches which focus on model architecture and design we may collectively describe them as part of a broader evasion-robust model design strategy. Some of the most commonly used methods are kTWA, gated batch norm layers and ensembles to name a few, yet they are still prone to attacks by highly determined threat actors. Not to mention that the combination of different defensive strategies : combining gradient masking with ensembles may result in better robustness.

References

Xiao, Chang, Peilin Zhong, and Changxi Zheng. “Enhancing Adversarial Defense by k-Winners-Take-All.” 8th International Conference on Learning Representations. 2020.

Liu, Aishan, et al. “Towards defending multiple adversarial perturbations via gated batch normalization.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2012.01654 (2020).

You, Zhonghui, et al. “Adversarial noise layer: Regularize neural network by adding noise.” 2019 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP). IEEE, 2019.

Athalye, Anish, Nicholas Carlini, and David Wagner. “Obfuscated gradients give a false sense of security: Circumventing defenses to adversarial examples.” International conference on machine learning. PMLR, 2018.

Useful standards include:

ISO/IEC TR 24029 (Assessment of the robustness of neural networks) Gap: this standard discusses general robustness and does not discuss robustness against adversarial inputs explicitly.

ENISA Securing Machine Learning Algorithms Annex C: “Choose and define a more resilient model design”

ENISA Securing Machine Learning Algorithms Annex C: “Reduce the information given by the model”

#TRAIN ADVERSARIAL

Category: development-time AI engineer control for input threats

Permalink: https://owaspai.org/go/trainadversarial/

Description

Train adversarial: Introducing adversarial examples into the training set and using them to train the model to be more robust against evasion attacks and/or data poisoning. First, adversarial examples are generated using one or more specific adversarial attack methods that have been defined in advance. These attacks are employed to create adversarial examples, such as using the PGD attack in Madry Adversarial Training.

Implementation

By definition, the model produces the wrong output for these adversarial examples. By introducing adversarial examples into the training set with the correct output, the model is essentially corrected. i.e., it is less affected by the perturbation from the adversarial attacks (in the production phase), and it may be able to generalize better over the data used in the production environment. In other words, by training the model on adversarial examples, it learns not to overly rely on subtle patterns in the data that might burden the model’s ability to predict/generalize well.

Note that adversarial samples may also be used as poisoned data, in which cases training with adversarial samples also mitigates data poisoning risk. On the other hand, it is important to note that generating the adversarial examples creates significant training overhead, does not scale well with model complexity / input dimension, can lead to overfitting and may not generalize well to new attack methods.

References

- For a general summary of adversarial training, see Bai et al.

- Goodfellow, I.J.; Shlens, J.; Szegedy, C. Explaining and harnessing adversarial examples. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1412.6572.

- Lyu, C.; Huang, K.; Liang, H.N. A unified gradient regularization family for adversarial examples. In Proceedings of the 2015 ICDM.

- Papernot, N.; Mcdaniel, P. Extending defensive distillation. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1705.05264.

- Vaishnavi, Pratik, Kevin Eykholt, and Amir Rahmati. “Transferring adversarial robustness through robust representation matching.” 31st USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 22). 2022.

- Tsipras, D., Santurkar, S., Engstrom, L., Turner, A., & Madry, A. (2018). Robustness may be at odds with accuracy. arXiv preprint arXiv:1805.12152.

Useful standards include:

- Not covered yet in ISO/IEC standards

- ENISA Securing Machine Learning Algorithms Annex C: “Add some adversarial examples to the training dataset”

#INPUT DISTORTION

Category: runtime AI engineer control for input threats

Permalink: https://owaspai.org/go/inputdistortion/

Description

Input distortion: The process of slightly modifying and/or adding noise to the input with the intent of distorting the adversarial attack, causing it to fail, while maintaining sufficient model correctness. Modification can be done by adding noise (randomization), smoothing or JPEG compression.

Implementation

Input distortion defenses are effective against both evasion attacks and data poisoning attacks.

Input distortion against Evasion Attacks

Evasion attacks rely on specific inputs that have been carefully prepared to give unwanted output. By distorting this input, chances are that the attack fails. Because all input is distorted, this can reduce model correctness. A way around that is to first use input without distortion and then one or more distortions of that input. If the results deviate strongly, it would indicate an evasion attack. In that case, the output of the distorted input can be used and optionally an alert generated. In all other cases, the undistorted input can be used, yielding the most correct result.

In addition, distorted input also hinders attackers searching for adversarial samples, where they rely on gradients. However, there are ways in which attackers can work around this. A specific defense method called Random Transformations (RT) introduces enough randomness into the input data to make it computationally difficult for attackers to create adversarial examples. This randomness is typically achieved by applying a random subset of input transformations with random parameters. Since multiple transformations are applied to each input sample, the model’s accuracy on regular data might drop, so the model needs to be retrained with these random transformations in place.

Note that zero-knowledge attacks do not rely on the gradients and are therefore not affected by shattered gradients, as they do not use the gradients to calculate the attack. Zero-knowledge attacks use only the input and the output of the model or whole AI system to calculate the adversarial input.

Input Distortion against Data Poisoning Attacks

Data poisoning attacks involve injecting malicious data into the training set to manipulate the model’s behavior, often by embedding/adding features that cause the model to behave incorrectly when encountering certain inputs, see 3.1.1 Data Poisoning. Input distortion defenses mitigate these attacks by disrupting the poisoning features embedded in the data, rendering them less effective.

Adversarial Samples: For data poisoning through adversarial samples, input distortion works similarly to how it defends against evasion attacks.

Other Poisoning Features: When the poisoning feature is brittle, e.g. a high-frequency noise the input distortion removes or breaks the pattern as is the case for adversarial samples, for example, slight JPEG compression can neutralize high-frequency noise-based poisons. If the poisoning feature is more distinct or robust, such as visible patches in images, the defense must apply stronger or more varied transformations. The randomness and strength of these transformations are key; if the same transformation is applied uniformly, the model might still learn the malicious pattern. Randomization also ensures that the model doesn’t consistently encounter the same poisoned feature, reducing the risk that it will learn to associate it with certain outputs.

See #EVASION INPUT HANDLING for an approach where the distorted input is used for detecting an adversarial attack.

References

- Weilin Xu, David Evans, Yanjun Qi. Feature Squeezing: Detecting Adversarial Examples in Deep Neural Networks. 2018 Network and Distributed System Security Symposium. 18-21 February, San Diego, California.

- Das, Nilaksh, et al. “Keeping the bad guys out: Protecting and vaccinating deep learning with jpeg compression.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1705.02900 (2017).

- He, Warren, et al. “Adversarial example defense: Ensembles of weak defenses are not strong.” 11th USENIX workshop on offensive technologies (WOOT 17). 2017.

- Xie, Cihang, et al. “Mitigating adversarial effects through randomization.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1711.01991 (2017).

- Raff, Edward, et al. “Barrage of random transforms for adversarially robust defense.” Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 2019.

- Mahmood, Kaleel, et al. “Beware the black-box: On the robustness of recent defenses to adversarial examples.” Entropy 23.10 (2021): 1359.

- Athalye, Anish, et al. “Synthesizing robust adversarial examples.” International conference on machine learning. PMLR, 2018.

- Athalye, Anish, Nicholas Carlini, and David Wagner. “Obfuscated gradients give a false sense of security: Circumventing defenses to adversarial examples.” International conference on machine learning. PMLR, 2018.

Useful standards include:

Not covered yet in ISO/IEC standards

ENISA Securing Machine Learning Algorithms Annex C: “Apply modifications on inputs”

#ADVERSARIAL ROBUST DISTILLATION

Category: development-time AI engineer control for input threats

Permalink: https://owaspai.org/go/adversarialrobustdistillation/

Description

Adversarial-robust distillation: defensive distillation involves training a student model to replicate the softened outputs of the teacher model, increasing the resilience of the student model to adversarial examples by smoothing the decision boundaries and making the model less sensitive to small perturbations in the input. Care must be taken when considering defensive distillation techniques, as security concerns have arisen about their effectiveness.

References

Papernot, Nicolas, et al. “Distillation as a defense to adversarial perturbations against deep neural networks.” 2016 IEEE symposium on security and privacy (SP). IEEE, 2016.

Carlini, Nicholas, and David Wagner. “Defensive distillation is not robust to adversarial examples.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1607.04311 (2016).

Useful standards include:

Not covered yet in ISO/IEC standards

ENISA Securing Machine Learning Algorithms Annex C: “Choose and define a more resilient model design”

2.1.1. Zero-knowledge evasion

Category: input threat

Permalink: https://owaspai.org/go/zeroknowledgeevasion/

Description

Zero-knowledge, or black box or closed-box Evasion attacks are methods where an attacker crafts an input to exploit a model without having any internal knowledge or access to that model’s implementation, including code, training set, parameters, and architecture. The term “black box” reflects the attacker’s perspective, viewing the model as a ‘closed box’ whose internal workings are unknown. This approach often requires experimenting with how the model responds to various inputs, as the attacker navigates this lack of transparency to identify and leverage potential vulnerabilities.

Since the attacker does not have access to the inner workings of the model, he cannot calculate the internal model gradients to efficiently create the adversarial inputs - in contrast to white-box or open-box attacks (see Perfect-knowledge Evasion).

Implementation

The zero-knowledge attack strategy to find successful attack inputs is query-based:

An attacker systematically queries the target model using carefully designed inputs and observes the resulting outputs to search for variations of input that lead to a false decision of the model. This approach enables the attacker to indirectly reconstruct or estimate the model’s decision boundaries, thereby facilitating the creation of inputs that can mislead the model. These attacks are categorized based on the type of output the model provides:

- Decision-based (or Label-based) attacks: where the model only reveals the top prediction label

- Score-based attacks: where the model discloses a score (like a softmax score), often in the form of a vector indicating the top-k predictions.In research typically models which output the whole vector are evaluated, but the output could also be restricted to e.g. top-10 vectors. The confidence scores provide more detailed feedback about how close the adversarial example is to succeeding, allowing for more precise adjustments. In a score-based scenario, an attacker can for example, approximate the gradient by evaluating the objective function values at two very close points.

Controls

See Evasion section for the controls.

References

Andriushchenko, Maksym, et al. “Square attack: a query-efficient black-box adversarial attack via random search.” European conference on computer vision. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2020.

Guo, Chuan, et al. “Simple black-box adversarial attacks.” International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR, 2019.

Bunzel, Niklas, and Lukas Graner. “A Concise Analysis of Pasting Attacks and their Impact on Image Classification.” 2023 53rd Annual IEEE/IFIP International Conference on Dependable Systems and Networks Workshops (DSN-W). IEEE, 2023.

Chen, Pin-Yu, et al. “Zoo: Zeroth order optimization based black-box attacks to deep neural networks without training substitute models.” Proceedings of the 10th ACM workshop on artificial intelligence and security. 2017.

Guo, Chuan, et al. “Simple black-box adversarial attacks.” International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR, 2019.

2.1.2. Perfect-knowledge evasion

Category: input threat

Permalink: https://owaspai.org/go/perfectknowledgeevasion/

Description

In perfect-knowledge or open-box or white-box attacks, the attacker knows the architecture, parameters, and weights of the target model. Therefore, the attacker has the ability to create input data designed to introduce errors in the model’s predictions. A famous example in this domain is the Fast Gradient Sign Method (FGSM) developed by Goodfellow et al. which demonstrates the efficiency of white-box attacks. FGSM operates by calculating a perturbation $p$ for a given image $x$ and it’s label $l$, following the equation $p = \varepsilon \textnormal{sign}(\nabla_x J(\theta, x, l))$, where $\nabla_x J(\cdot, \cdot, \cdot)$ is the gradient of the cost function with respect to the input, computed via backpropagation. The model’s parameters are denoted by $\theta$ and $\varepsilon$ is a scalar defining the perturbation’s magnitude. Even attacks against certified defenses are possible.

In contrast to perfect-knowledge attacks, zero-knowledge attacks operate without direct access to the inner workings of the model and therefore without access to the gradients. Instead of exploiting detailed knowledge, zero-knowledge attackers must rely on output observations to infer how to effectively craft adversarial examples.

Controls

See Evasion section for the controls.

References

- Goodfellow, Ian J., Jonathon Shlens, and Christian Szegedy. “Explaining and harnessing adversarial examples.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1412.6572 (2014).

- Madry, Aleksander, et al. “Towards deep learning models resistant to adversarial attacks.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1706.06083 (2017).

- Ghiasi, Amin, Ali Shafahi, and Tom Goldstein. “Breaking certified defenses: Semantic adversarial examples with spoofed robustness certificates.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2003.08937 (2020).

- Hirano, Hokuto, and Kazuhiro Takemoto. “Simple iterative method for generating targeted universal adversarial perturbations.” Algorithms 13.11 (2020): 268.

- Eykholt, Kevin, et al. “Robust physical-world attacks on deep learning visual classification.” Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. 2018.

2.1.3 Transferability-based evasion

Category: input threat

Permalink: https://owaspai.org/go/transferattack/

Description

Attackers can execute a transferability-based attack in a zero-knowledge situation by first creating adversarial examples using a surrogate model: a copy or approximation of the target model, and then applying these adversarial examples to the target model. The surrogate model can be:

- a perfect-knowlegde model from another supplier that performs a similar task (e.g., recognize traffic signs) - showing all its internals,

- a zero-knowledge model from another supplier that performs a similar task - accessible through for example an API, (e.g., recognize traffic signs),

- a perfect-knowledge model that the attacker trained based on available or self-collected or self-labeled data,

- the exact target model that was stolen development-time or runtime,

- the exact target model obtained by purchasing or free downloading,

- a replica of the model, created by [Model exfiltration attack])/go/modelexfiltration/)

The advantage of a surrogate model is that it exposes its internals (with the exception of the zero-knowledge surrogate model), allowing an Perfect-knowledge attack. But even a closed models may be beneficial in case detection mechanisms and rate limiting are less strict than the target model - making a zero-knowledge attack easier and quicker to perform,